Geodesign - Ancient concept, universal applications, modern tools

Geodesign is ingrained in every landscape modification everywhere, some more successfully than others. The ancient Chinese called it Feng-shui. The Anasazi built their cliff-dwellings at Mesa Verde to catch the morning sun in mid-winter. Frank Lloyd Wright ‘designed with nature’ at Taliesin in Wisconsin and Fallingwater in Pennsylvania. And golf course designers everywhere - as evidenced by Michael Hill’s turf-covered clubhouse in Arrowtown - maximise the appeal of their layout by working with the existing contours.

Geodesign is both a new technology and an old concept. At the inaugural Geodesign Summit held in 2010, contributors variously defined Geodesign as “designing with nature in mind” and “changing geography by design”. At its core is the principal that design should adhere to the natural landscape to lessen environmental impact, achieved through comparing and sharing designs, factoring in the unique attributes of a site and inviting public consultation and collaboration.

"GeoDesign and urban planning are probably the same thing," said Atanas Entchev of ENTCHEV GIS Architects. "An urban planner who uses GIS daily to its full potential (I know none) is probably a GeoDesigner. GeoDesign brings a fascinating set of tools to the urban planning profession.” Directions Magazine March 11 2010

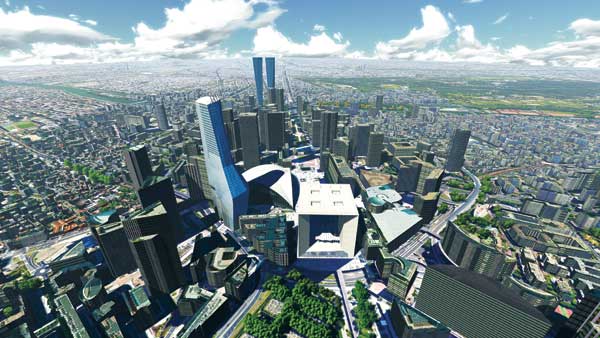

Geodesign in practice has been around as long as humans have had digging sticks and stone walls. Today’s landscape architects specialise in submitting plans, maps and reports that take advantage of the integration of 3D renderings with the more traditional 2D maps. But they may have to send the data around several different software packages before they can create the final graphics. And field-based interactivity in real time - the ability to see the simulated effects as you stand where the project will take place - is only just starting to become available.

Geodesign in New Zealand

Practitioners of GIS in New Zealand - local and regional councils, central government, developers, planners, farmers and others - use the tools available to anticipate how any changes to the landscape - be it a new footpath, an application of fertiliser close to a stream or a proposed convention centre - will affect the stakeholders of that landscape.

But until now, the tools that link design and GIS have not been readily available. We can produce any number of colourful maps with all sorts of options, costings and potential ramifications. We can map view-sheds, watersheds and backyard sheds. We can add amazing graphics to submissions, proposals and reports. Mapping has never been as prevalent as it is now. But only now is technology catching up with the geodesign concept (see sidebar 1). Today’s GIS tools are faster, more powerful, more mobile, less expensive to acquire and easier to use. No longer the preserve of trained geographers, GIS is becoming mainstream. Everyone uses Google Earth and interactive maps are features on web sites around the world. And with all of this new technology, geodesign is becoming a viable automated process.

Among a range of tools informing geodesign is Esri’s ArcGIS platform. Cloud services and the advent of Web GIS put a range of collaborative and authoritative tools in the hands of planners, landscape architects, engineers and the public. ArcGIS Online is a subscription service that enables a vast and increasing repository of data to be accessed and it’s not just Esri data, but data submitted from a vast number of users from diverse organisations. It includes information such as ocean terrain analysis, environmental impact maps, seismic data, flood prone districts, sea level predictions and fire risk zones. Planners can sketch their designs into scenarios and immediately see the impact of the design on the landscape, or in the context of the available data, very early in the process.

Collaboration using Geodesign

Until now, the ability for stakeholders to collaborate on planning changes to the landscape has been limited. Typically ‘designing with nature’ has been a one-way street. Planners design, builders build and societies live with the result. This is now changing with designers able to publish interim plans, maps and 3D renderings to the web to solicit feedback. GIS is making the planning process less autocratic and more democratic.

Today’s tools, such as Esri’s ArcGIS Online and powerful handheld tablets, can display simulations in real time and in the field. We can now visualise how proposed modifications will interact with the landscape. If you are buying a new chair for your lounge, you’ll hold up a swatch of fabric to see colour compatibility with your curtains. This is micro-geodesign. Why shouldn’t you be able to visualise and then change the proposed colour or height of a building when you are standing across the street or on a hill overlooking where the footers will go? You shouldn’t have to go back to the office to plot another rendering. Forward-looking organisations are taking advantage of the nexus of a new generation of tools - faster more powerful tablets and laptops, online GIS interfaces and backend processors and advanced 3D design and display tools - to deliver on the promise of geodesign. One such development is Esri’s GeoPlanner app, designed to be easy to use for non-GIS users (e.g. Landscape Architects, Planners, Scientists, Students, Policy Makers, Analysts, Educators, etc.), which can be configured for use across a wide range of industries.

“Esri has been working on embedding geodesign principles into their software packages since their very earliest days,” says Matt Lythe, GIS Sale Manager at Eagle Technology, the exclusive distributor (since 1986) of Esri ArcGIS software in New Zealand. “But the amount of ‘grunt’ to render complicated graphics quickly was a stumbling block. Even to make a simple modification to a building height has required every vector, point and polygon to be re-processed before it can be displayed. In the past, powerful servers have been required and even then you could get a cup of coffee while you waited. But those days are over. Here in New Zealand GIS has been used to support urban planning for years. And in more recent times geodesign tools such as ArcGIS 3D Analyst and Esri CityEngine have been used by councils such as Porirua City, Hastings District Council, Wellington City and Auckland Council to plan infrastructure and assess district plan suitability.”

Esri President Jack Dangermond notes, “the experience Esri gained while developing CAD integration tools, ArcSketch, and the tools in ArcGIS 10 has led to an appreciation of the power that can be derived from by associating drawing tools, symbology, data models and process models into one integrated framework for doing Geodesign. (ArcNews, Summer 2009)

The amount of processing power in today’s handheld devices can drive complicated graphics. Fast internet and 4G telecommunications means that we can send and receive massive amounts of data through the airwaves. And advances in shared mapping interfaces have given us the tools to collaborate in near real time. All of these factors have combined to give geospatial specialists - surveyors, planners, environmentalists - the tools to visualise the impact of changes to the landscape. Will this result in a more sustainable future? Maybe. But at least geodesign will give us the ability to simulate, in advance, what the future will hold.